Large scale agricultural land acquisitions are generating conflicts and controversies around the world. A growing body of reports show that these projects are bad for local communities and that they promote the wrong kind of agriculture for a world in the grips of serious food and environmental crises. 1 Yet funds continue to flow to overseas farmland like iron to a magnet. Why? Because of the financial returns. And some of the biggest players looking to profit from farmland are pension funds, with billions of dollars invested.

Pension funds currently juggle US$23 trillion in assets, of which some US$100 billion are believed to be invested in commodities. Of this money in commodities, some US$5–15 billion are reportedly going into farmland acquisitions. By 2015, these commodity and farmland investments are expected to double.

Pension funds are currently juggling US$23 trillion in assets. Some US$100 billion of this is believed to be invested in commodities. Of this, some US$5–15 billion is reportedly going into agricultural land acquisitions. By 2015, these figures are expected to double.

Pension funds are supposed to be working for workers, helping to keep their retirement savings safe until a later date. For this reason alone, there should be a level of public or other accountability involved when it comes to investment strategies and decisions. In other words, pension funds may be one of the few classes of land grabbers that people can pull the plug on, by sheer virtue of the fact that it is their money. This makes pension funds a particularly important target for action by social movements, labour groups and citizens’ organisations.

The size & weight of pensions

Today, people’s pensions are often managed by private companies on behalf of unions, governments, individuals or employers. These companies are responsible for safeguarding and “growing” people’s pension savings, so that these can be paid out to workers in monthly cheques after they retire. Anyone lucky enough both to have a job and to be able to squirrel away some income for retirement probably has a pension being administered by one firm or another. Globally, this is big money. Pension funds are currently juggling US$23 trillion in assets. The biggest pension funds in the world are those held by governments, such as Japan, Norway, the Netherlands, Korea and the US (see Table 1).

Table 1: World’s top 20 pension funds (2010)

Rank Fund Country Total assets (US$ millions)

1 Government Pension Investment Japan 1,315,071

2 Government Pension Fund–Global Norway 475,859

3 ABP Netherlands 299,873

4 National Pension Korea 234,946

5 Federal Retirement Thrift US 234,404

6 California Public Employees US 198,765

7 Local Government Officials Japan 164510

8 California State Teachers US 130,461

9 New York State Common US 125,692

10 PFZW (now PGGM) Netherlands 123,390

11 Central Provident Fund Singapore 122,497

12 Canada Pension Canada 122,067

13 Florida State Board US 114,663

14 National Social Security China 113,716

15 Pension Fund Association Japan 113,364

16 ATP Denmark 111,887

17 New York City Retirement US 111,669

18 GEPF South Africa 110,976

19 Employees Provident Fund Malaysia 109,002

20 General Motors US 99,200

Source: Pensions & Investments, 6 September 2010, P&I/Towers Watson World 300

Pensions – both the institutionally managed and individually held retirement accounts – were hit hard by the recent financial crisis, particularly in the West. As a consequence, provident funds and pension managers are seeking to rebuild long-term holdings for their clients. Farmland is a big attraction for them. They see in farmland what they call good “fundamentals”: a clear economic pattern of supply and demand, which in this case hinges on a rising world population needing to be fed, and the resources to feed these people being finite. Fund managers see land prices relatively low in places such as Australia, Sudan, Uruguay, Russia, Zambia or Brazil. They see those prices moving in sync with inflation (and, importantly, wages) but not with other commodities in their investment portfolios, thus providing a diversified income stream. They see long-term pay-offs from the rising value of farmland and the cash flow that will in the meantime come from crop sales, dairy herds or meat production. If you were holding on to money that had to be paid out to workers 30 years from now, you too could see the logic.

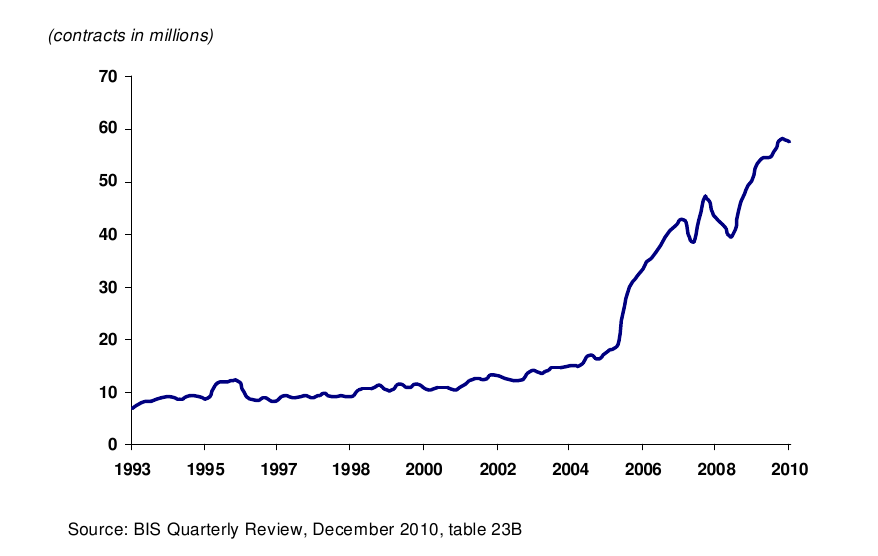

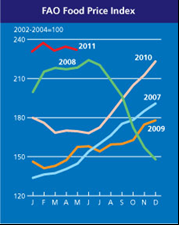

Scale is one factor that makes the role of these funds important. Pension funds started investing in commodities, including food and farmland, only recently. 3 With both commodities and food prices so steeply on the rise (see Graph 1), agriculture is one clear and unmistakable source of pay-off for institutional investors. 4

Graph 1: Making money from agriculture – trading on commodity exchanges (L) and food prices (R) both surging

Sources: Bank for International Settlements (L) and UN Food and Agriculture Organisation (R)

According to Barclays Capital, some US$320 billion of institutional funds are now invested in commodities, compared to just US$6 billion ten years ago. Hedge funds account for an additional US$60–100 billion. These figures are expected to double in the next few years. 5

Within this panorama, pension funds are said to be the biggest institutional investors in both commodities in general (US$100 billion of the US$320 billion indicated above) and farmland in particular. 6 According to numerous surveys within the industry, pension fund managers are seeking to invest in farmland – a new asset class offering annual returns of 10–20% – as never before. 7 This won’t surprise anyone who has been monitoring the big “ag investment” seminars being held in posh hotels from Zurich to London to New York to Singapore over the last three years. Take the Global AgInvesting Conference held at the Waldorf Astoria in Manhattan just last month: the conference attracted about 600 investors, from Bunge to Deutsche Bank. Collectively, this group represented holdings of US$10.8 billion in agricultural assets worldwide, with plans to raise those holdings to US$18.1 billion (up 67%) over the next three years. Farmland is at the centre of the acquisition strategy for many of these firms. Nearly one-third (30%) of them were pension funds.

Pension funds may be one of the few classes of land grabbers that people can pull the plug on, by sheer virtue of the fact that it is their money.

Today, commodities like farmland make up, on average, 1–3% of pension funds’ portfolios. 8 Yet by 2015, strategy decisions being taken now are expected to boost this to 3–5%, the “new optimal”. 9 While figures of one, three or five per cent may sound terribly small, these are huge funds, where one per cent may amount to several billion dollars. Table 2 tries to go a bit deeper and examine some sample farmland portfolios of pension fund managers. But, as so often, the data are opaque and hard to come by.

Table 2: Examples of pension funds investing in farmland (2010–2011)

Fund Total assets under management (AUM) Global farmland investment portion…(% of AUM) …and its status

AP2 (Second Swedish National Pension Fund) SEK220 billion

[US$34.6 billion] US$500 million in grain farmlands in US, Australia and Brazil (1.4%) Planned joint venture with TIAA–CREF.Firstforays into farmland investing were in 2010

APG (administering the National Civil Pension Fund), Netherlands €220 billion

[US$314 billion] €1 billion (0.5%)

[US$1.4 billion] A planned increase

Ascension Health, USA US$15 billion Up to US$1.1 billion (7.5% target) Looking to invest in farmland for the first time, to help meet a real assets target of 7.5% that is currently underachieved

CalPERS (California Public Employees’ Retirement System), USA US$231.4 billion About US$50 million (0.2%):

– US$1.2 million directly invested in Black Earth Farming

– US$47.5 million invested in agribusiness firms with huge int’l farmland holdings: Golden Agriresources, Indofood, IOI Corp, Olam, Sime Darby, Wilmar Current

Dow Chemical, USA

not revealed Farmland addedrecently. Aimed annual returns on US holdings: 8–12%

New Zealand Superannuation Fund NZ$17.43 billion

[US$14.2 billion] NZ$500 million (3%)

[US$407 million] The 3% allocationhasbeenmade at the Fund’s strategy level. First purchases into domestic farmland have started, to be followed by overseas farmland holdings

one US “state teachers fund” (CalSTRS?)

US$500million–US$1billion

PGGM (Pension Fund for Care and Well-Being), Netherlands €90 billion

[US$128 billion] not revealed Mayraise farmland allocation in 2011

PKA (Pensionskassernes Administration), Denmark US$25 billion US$370 million (1.5%) ByApril 2012. In June 2011, made a first placementof US$50 million in SilverStreet Capital’s Luxembourg-based Silverland Fund, targeting primarily Zambia

some “national government employees pension fund”

US2–5 billion Plannedsoon

Sonoma County Employees’ Retirement System Association, USA

Expected to allocate 3% toUBSAgrivestFarmlandFund

TIAA–CREF (Teachers Insurance & Annuity Association – College Retirement Equities Fund), USA US$426 billion US$2 billion in400 farms in North and South America, Australia and Eastern Europe (0.5%) Current. They claim annual returns of 10%

Calling them down

The big picture shows that:

1. the largest institutional investors are planning to double their portfolio holdings in agricultural commodities, including farmland;

2. they are reportedly going to do it very soon;

3. the new surge in money will push up global food prices;

4. high food prices will hit poor, rural and working-class communities hard.

It may not be easy to influence pension fund managers themselves. After all, they have no objective other than to make money – including their own cut – with the funds handed to them. But surely labour unions, employee-benefits planning bodies, pension boards, governments, and others who are responsible for strategy decisions about how pensions should be invested and grown can and should be persuaded to divest from farmland and other agricultural commodities.

One recent experience in the US, recounted by Sarah Anderson of the Institute for Policy Studies, gives a good example:

A coalition of family farm, faith-based and anti-hunger groups, along with business associations, have initiated a campaign to persuade investors to pull out of commodity index funds. Their first target: CALSTRS, the California teachers’ retirement system, which had been considering shifting $2.5 billion of their portfolio into commodities. In response to the divestment campaign, the CALSTRS board decided on November 4 to adopt a different strategy. Instead of $2.5 billion, they will invest no more than $150 million in commodities for 18 months, while further studying the potential problems. 10

Such divestment campaigns – which could aim at ensuring that pension funds do not buy into agricultural land overseas – are clearly within reach and could make a difference. And they can add their weight to the broader momentum under way in so many of our countries to rethink two vital matters: food and agricultural policies, which require constructive investment strategies; and retirement systems in general. There is too much at stake not to seize these opportunities

Going further

The website farmlandgrab.org is regularly updated with articles and news about pension funds going into farmland. Seehttp://farmlandgrab.org/search?query=pension+fund&sort_order=date for a direct view. It also provides a wealth of contacts and reports of people’s experiences in dealing with the global rush to get control over farmland, in the context of the current food crisis.

Watch a presentation by Jose Minaya of TIAA-CREF at the World Bank’s land conference in April 2011: http://vimeo.com/23314644

Endnotes

1 See the materials from the international conference on Global Land Grabbing held on 6–8 April 2011 at the Institute for Development Studies, University of Sussex, UK, http://www.future-agricultures.org/index.php?option=com_content&view=category&layout=blog&id=1547&Itemid=978. See also John Vidal’s reports for the Guardian(http://www.guardian.co.uk/world/2011/mar/21/ ethiopia-centre-global-farmland-rush); Alexis Marant’s film Planet for Sale(http://farmlandgrab.org/post/view/18542); the studies on land deals in Africa being released by the Oakland Institute (http://media.oaklandinstitute.org/land-deals-africa); the Dakar Appeal against land grabbing, drawn up by participants at the World Social Forum in February 2011 and presented to the G20 agriculture ministers in June 2011 (https://viacampesina.org/en/index.php?option=com_content&view=category&layout=blog&id=23&Itemid=36); and the collective statement against “responsible” agricultural land investments launched by La Via Campesina, FIAN, LRAN, WFF and GRAIN in April 2011 (http://www.grain.org/nfg/?id=767).

2 Sovereign wealth funds, by comparison, hold about US$4 trillion in assets.

3 Commodities are basic goods and services that are bought and sold in bulk – such as oil, gold, rice, coffee, copper or beef. “Basic” means that they can be used, like raw materials, to make other goods or services. And “in bulk” means that the item can be pooled from various sources, with a high level of uniformity. Thus a sack of rice or a barrel of oil may be composed of rice or oil coming from various fields or pumps, as long as they have similar basic qualities. Commodities, following the breakdown used by onValues Investment Strategies and Research in a recent report for the Swiss government, are often traded today in the form of futures contracts, physical stocks, so-called “real” assets (like land) and equity in firms that hold productive assets. See Ivo Knoepfel, “Responsible investment in commodities: the issues at stake and a potential role for institutional investors”, project co-sponsored by the Swiss Confederation, PRI and Global Compact, Zurich, January 2011, p. 3 (available athttp://farmlandgrab.org/post/view/18339).

4 Though some still try to deny it, many people – from investment bankers to civil society organisations (CSOs) – have argued and shown how commodity investors are in fact fuelling the current food-price hikes, particularly since the financial meltdown of 2008. Some recent accessible CSO analysis on the matter include the World Development Movement’s work on food speculation (http://www.wdm.org.uk/food-speculation) and material prepared for Oxfam’s GROW campaign (http://www.oxfam.org/en/grow).

5 See Ivo Knoepfel, op. Cit., p. 2.

6 Ibid., p 16.

7 Many of these land deals are not investments in any productive economic sense. Rather, they are financial schemes to generate returns on capital in the form of rent. See the analysis by Hubert Cochet and Michel Merlet, “Land grabbing and share of the value added in agricultural processes. A new look at the distribution of land revenues”, paper presented at the international conference on Global Land Grabbing at the Institute of Development Studies, University of Sussex, UK, 6–8 April 2011,http://www.future-agricultures.org/index.php?option=com_docman&task=doc_download&gid=1174&Itemid=971

8 Some of the biggest funds allocate as much as 7% of their portfolios to commodities.

9 Knoepfel, op. cit., p. 14.

10 Sarah Anderson, “Food shouldn’t be a poker chip”, IPS, Washington DC, 15 November 2010, http://www.ips-dc.org/articles/food_shouldnt_be_a_poker_chip. For more information, see “Stop gambling on hunger”, http://stopgamblingonhunger.com/?page_id=838