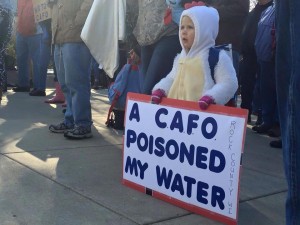

MADISON — People opposed to the expansion of concentrated animal feeding operations in Wisconsin brought their message to the state Capitol steps Nov. 7 with what they called a “Stink In” protest.

About 100 people representing more than 20 organizations gathered for the event, some dressed in cow and turkey costumes, to address what they described as the state’s “CAFO crisis and its damaging impact on public health, water and air quality, natural resources, businesses, property values and rural community life.”

Mary Dougherty, co-founder of Farms Not Factories and one of the event organizers, said it was fitting that the protest be held on the Capitol steps, since “the proliferation of CAFOs started in Madison with ATCP 51.”

Wisconsin’s livestock-facility-siting law, passed by the state Legislature in 2003, directed the Wisconsin Department of Agriculture, Trade and Consumer Protection to create rules regarding the siting of livestock facilities in the state. Those rules became known as ATCP 51 and took effect in 2006. They set standards for siting new and expanding facilities in areas of the state zoned for agricultural uses and on livestock operations expected to house more than 500 animal units.

Dougherty, who has been active in opposing the siting of a proposed 26,000-hog farm in Bayfield County, said the siting law caused an “explosion” of CAFOs that has reached about 300 farms in Wisconsin in 2015.

“These large farms are not something the citizens of Wisconsin are necessarily benefiting from,” Dougherty said. “These farms have been granted regulatory certainty at the expense of local communities. We would like our elected officials to listen to us — we need them to help us figure this thing out.”

Dougherty said with an issue such as CAFOs, no one person can come up with a solution on his or her own.

“But a group of people invested in the community, with the environment and economic development in mind, we can come up with something really solid that everyone can live with,” she said. “That’s all we’re asking.”

Organizers developed a five-point request to lawmakers: raise their awareness on the community impacts of CAFOs; support enforcement of health and environmental standards allegedly violated by some of the state’s CAFOs; champion upgrades in the Department of Natural Resources’ capacity to enforce the law; ensure that regulations and safeguards are in place to protect Wisconsin communities from CAFO contamination threats; and engage in “open, impartial and sensible dialogue with impacted Wisconsin communities to seek workable solutions for CAFO-created public risks.”

Scott Dye, regional coordinator for Socially Responsible Agricultural Projects, became active in the large-farm debate after an 80,000-hog farm located next to his family’s farm in Missouri.

“The livestock-facility-siting law has been an abysmal, atrocious act for these local communities in Wisconsin,” Dye said. “One size does not fit all, certainly when you’re looking at the karst topography in Green County, where a farmer wants to build a 5,000-cow dairy, or that god-awful mess in Kewaunee County. Literally 30 percent of the private wells in the county are polluted. It makes you wonder how things could go so horribly wrong.”

The Tuls family is proposing to build a large dairy farm in Green County, which would be the fourth for the family. The family already has two large dairies in Nebraska and a farm near Janesville.

About 300 people attended a Nov. 3 meeting in Monroe to learn more about the Green County proposal.

“The average-sized dairy herd in Green County is something like 67 cows, so how many of those herds is a 5,000-cow dairy going to put out of business?” Dye said. “What does Wisconsin want to see in the future in the countryside? Do people want to be serfs pushing buttons and putting manure into a hole in the ground, or do they want to be a strong agricultural state, as Wisconsin has traditionally been?”

Several organizers were critical of the Dairy Business Association, a Wisconsin-based organization of dairy farmers, which they said has helped facilitate the movement to larger farms.

Tim Trotter, DBA’s executive director, said the organization has never changed its position of supporting family farms in any way possible.

“Farmers make their decisions based on family and the land base they have, and they make economic and agronomic decisions that best suit the mission of their family,” Trotter said. “We represent small and large farms alike — they are all vital to the Wisconsin dairy industry. It is short-sighted to judge a family farm based on its size. CAFOs have more stringent regulations (than small farms), and they are some of the most environmentally friendly operations there are.”

The argument that the size of an operation determines a farm’s environmental sensitivity “doesn’t hold up,” Trotter said.

“It comes back to the science,” he said. “When you get a site permit, you have to adhere to the law developed by our state Legislature.

“To me it’s all about communications and understanding. There’s a communication gap between agriculture and consumers in general. What we’re seeing is a symptom of that. A lot of people don’t understand what goes on on a farm today. In absence of knowledge, people often make assumptions, and sometimes assumptions can be dangerous.”

John Peck, executive director of the Madison-based Family Farm Defenders, said the livestock-siting law streamlined the process for farmers to get permits to expand or site new CAFOs.

“The hearings (for siting permits) are a joke,” Peck said. “A permitting process where no one gets rejected is not really a permitting process.”

Peck said farm groups such as his have been looking for a legislator or legislators to challenge the livestock-siting law.

“It seems to be really difficult to find anyone,” Peck said. “The rally was really encouraging. I’m glad to see people are starting to question the law. We’re hoping the (Environmental Protection Agency) will do something if the DNR won’t.”

Dougherty said although rally organizers haven’t been successful in getting a legislator to champion the cause, they haven’t given up on the possibility.

“(Taking the issue to the Legislature) is probably two or three steps down the road,” Dougherty said. “We’re looking for that one champion who will have the courage to do what needs to be done.”

Dougherty said the movement hasn’t gained the groundswell necessary to show legislators who might step up on the issue that their constituents “have their back.”

“It’s David vs. Goliath — it’s going to take a lot of work,” Dougherty said. “We are people who just want to protect our homes from an industry that is poisoning our homes. If it can happen anywhere, I do believe it is in the state of Wisconsin. I think we can pull it off.”

Dougherty said she anticipates having another “Stink In” in Green Bay, perhaps in the spring, and other events to try to gain more visibility for the issue.