By: Anthony Pahnke, FFD vice president and an associate professor of international relations at San Francisco State University.

Originally published in the Hill, 8/6/23

Food security is national security.

That has been one justification used by some legislators, from North Dakota to Florida, who have launched a series of initiatives that seek to curtail foreign purchases of farmland. At the federal level, similar legislation would scrutinize prospective land deals by Chinese interests looking to become involved in U.S. agriculture. And most recently, the National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) was passed with a limitation placed on purchases by any actor from China, Russia, North Korea and Iran to 320 acres or that has a value of over $5 million.

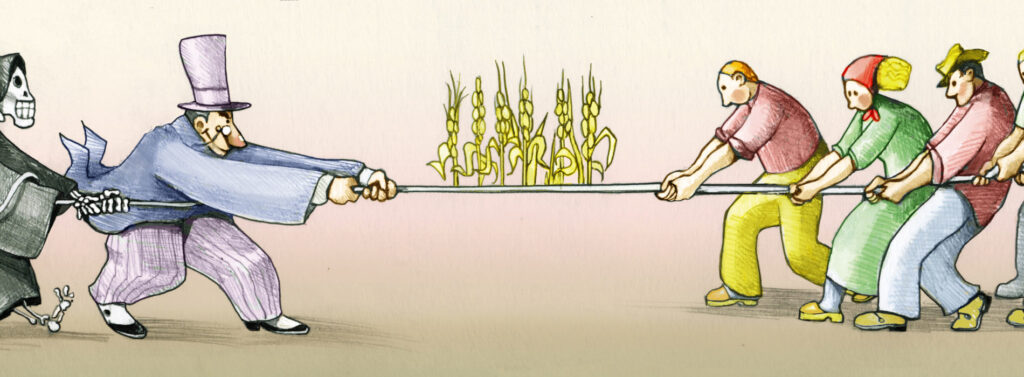

But there’s a problem — corporations are let off the hook.

For instance, the number of properties in the United States owned by corporations and financial services firms rose three-fold from 2009 to 2022, as the market value of those properties increased from under $2 billion to over $14 billion during that same time. Meanwhile, land values are soaring, rising by 14 percent from 2021 to 2022 alone. This, as 40 percent of farmland in projected to change hands over the next 20 years as farmers age out of the profession and new farmers struggle to replace them.

According to a 2022 survey of over 10,000 beginning producers conducted by the National Young Farmers Coalition, the principle challenge impeding the next generation of farmers is the high cost of land.

Addressing such dynamics makes the Farmland for Farmers Act, which was recently introduced by Sen. Cory Booker (D-N.J.), so critical.

Particularly, this initiative would ban corporations – both foreign and domestic — from acquiring farmland. With respect to promoting food security, in seeking to check corporate power, this legislation would remove one critical, emerging force that is making accessing land next to impossible for our next generation of food producers.

Another concern with respect to food security, besides driving up land prices and making access difficult, is how corporate land purchases tend to favor the development of large-scale monocultural operations. Globally, this has been the trend, with firms around the world not buying land to start diversified operations for local food production, but to focus on planting and then harvesting thousands upon thousands of acres of commodity crops such as corn and soy.

Such investments, according to some investment firms themselves, are wise because they appear inflation-proof and safe with respect to generating returns. After all, people need to eat, and farmland is a finite resource — moreover, one that is disappearing as climate change triggers extreme weather events such as floods, which leads to erosion and removes land from production.

But what may be good for a corporation’s bottom line may not be what’s best for the country’s food system and our nation’s dietary needs.

While corn and soy end up as food, they usually appear in the form of processed foods, such as high fructose corn syrup that is used in soda, candy and fast food. These items end up composing some of the primary sources of nutrition for people who live in food deserts, where in rural and urban areas, access to grocery stores is limited, and many rely on convenient stores and sometimes gas stations for sustenance. Meanwhile, over 75 percent of soy harvested finds its way into animal feed — with approximately half of total U.S. production being exported.

These dynamics contribute to food insecurity, which according to the USDA, is the limited or uncertain availability of nutritionally adequate and safe foods, or limited or uncertain ability to acquire acceptable foods in socially acceptable ways. In 2021, the USDA estimated that over 10 percent of American families were food insecure. More recently, with rising inflation and the end of pandemic benefits, others place that figure closer to 25 percent.

The Farmland for Farmers Act neither establishes a way for farmers to access land, nor directly supports local production. What the bill does, in banning corporations from purchasing farmland, is remove one factor that raises farmland prices and that promotes monoculture. As such, it improves the chances for beginning, small-scale producers to access land and produce food for themselves and their communities. Furthermore, the Act does provide for some flexibility, as some farmers decide to form corporations themselves as a way to mitigate risk among family members and pool resources. These entities are exempt from the proposal, as corporations with only over 25 members are subject to the ban.

Besides land, the Act also prohibits corporate entities from receiving federal assistance, which some large-scale corporations accessed as a result of Trump administration’s trade war with China. Such a stipulation assures that resources go to actual farmers, potentially to support locally focused, sustainable operations, which programs like the Environmental Quality Incentives Program (EQIP) finance.

In terms of the Farmland for Farmers Act’s path, it could find its way through Congress and become a stand-alone piece of legislation. It is more likely to become part of the Farm Bill, which is currently being drafted.

Corporate farmland investment is not the only driver of food insecurity, but it certainly doesn’t help. Meanwhile, all the attention given to blocking Chinese farmland acquisitions seem more like xenophobic hysterics meant to gin up the public than representing a true concern with promoting agriculture. So, if food security is really a worry, let’s give farmers a chance to produce food for their communities. Let’s ban corporate land investments before they dominate any more of our food and farm system.