By Anthony Pahnke, Vice President, Family Farm Defenders

Originally Published by Civil Eats, Jan. 13th, 2022

As an organizer working with farm groups in Wisconsin, I have asked many poultry farmers about the conditions they’re working under. Sadly, no one will speak to me.

It’s not that I’m unfriendly. In fact, I regularly speak to dairy and vegetable farmers about their problems, and most producers are more than willing to talk about their challenges and share their experiences with me.

But poultry farmers display a unique type of fear. Not of me—but of their industry. Poultry farmers work on contract with larger companies and the contracts they sign require that they raise the birds provided by the company, to the specs it provides and in a set window. The poultry industry is so concentrated, that the lack of competing buyers allows agribusiness processors total control to dictate the price, the farm conditions, the building specifics, and the feed every farmer must use. And farmers often go deeply into debt to meet those requirements.

In this environment, farmers are scared, not just to speak to me, but to talk to anyone about how hard it is for them to get by. And yet, most feel they have no choice but to continue working for the small handful of companies that now control the industry.

Concentration in agriculture is—and has been—a problem in American agriculture for years. The documentary Food, Inc. famously featured several contract poultry farmers trapped under crippling debt and unable to change their practices for the better. In 2010, many former and current farmers testified at public hearings that the Department of Justice (DOJ) and the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) held on the poultry industry. They spoke out about consolidation, vertical integration, and the debt they had taken on to stay in the business.

John Oliver also ran a powerful segment about the conditions back in 2015. And yet nothing significant has changed since then.

So, it was a promising development when, earlier this month, President Biden, Agriculture Secretary Tom Vilsack, and representatives from a number of farm groups came together to announce a plan to “boost competition in the meat industry.”

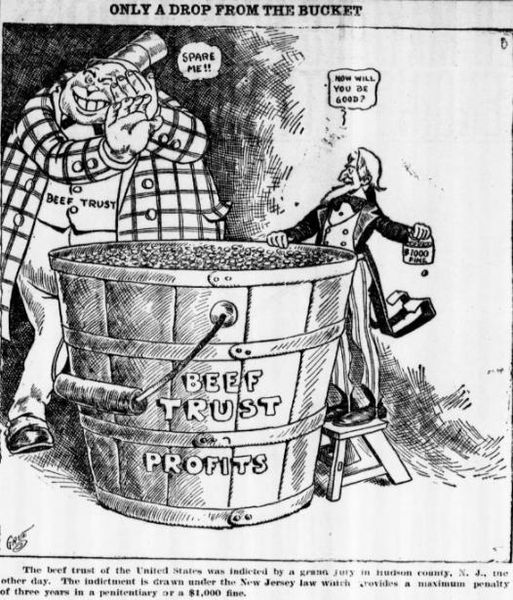

At the core of the plan is the allocation of $1 billion to assist independent meat processors and ranchers to become more competitive within the larger industry. In Biden’s own words, “capitalism without competition isn’t capitalism, it’s exploitation.”

While it’s a good first move, not only in recognizing the problem, but also in dedicating resources to the matter, the truth is that it’s far from enough. In addition to supporting independent producers, the administration, and more specifically the USDA, must make a sincere attempt to improve the rules of the game. Or rather, to ensure that our agricultural markets ensure fair competition.

We know that our food and farm systems lack such dynamics.

A study out of the University of Missouri found that when four firms control more than 45 percent of any given sector of the economy, those entities with market share show a proclivity to engage in anti-competitive practices that hurt farmers, workers, and consumers. Such practices include price and wage fixing, as well as dictating conditions to buyers and sellers. Additionally, innovation declines as, with fewer and fewer actors involved in some market, competition is replaced by collusion.

According to the Open Markets Institute, over the last three decades, the four largest poultry processors went from holding 35 to 51 percent of total market share, while in beef processing, that figure went from 25 to 85 percent, and in hogs, it went from 33 to 66 percent. The dairy industry, as of 2017, saw its four largest cooperatives control over 53 percent of all unprocessed raw milk sales.

Biden isn’t proposing paying farmers directly—his $1 billion investment is to help create more processing facilities, which could improve competition by offering farmers and ranchers more options when it comes to processing and sell their livestock.

But $1 billion in new investments may turn out to be a drop in the bucket considering the larger scope of consolidation within the meat and dairy industries.

The last few U.S. Agricultural Censuses show these dynamics, as there were 1.2 million cattle ranchers in 1997, and now they number just over 880,000. This decline by about a third over a span of 15 years pales in comparison to what we see in dairy, when in 1997, there were more than 125,000 licensed herds and in 2017 just about 54,000.

Technological changes, from genetics to improvements in milking, play a partial role in how the number of farms around the country has decreased at the same time as consumers stay fed. Yet, there’s also the fact that consolidated supply chains are prone to price-fixing, which leads powerful actors to depress prices for farmers and pay for workers. This is why, according to the National Farmers Union, U.S. farmers receive just 14 cents of every food retail dollar.

There’s also the series of supply chain disruptions that the COVID-19 pandemic caused, which should make us rethink the wisdom of letting our food and farm system become so consolidated.

From workers at meatpacking companies who have to remain on the job and risk serious illness and death, to the exorbitant amounts of waste that came from processors unable to adapt to changes in consumption patterns, U.S. agriculture has shown itself as exploitative and irrational over the last two years.

As Attorney General Merrick Garland pointed out in his comments at the January 3 roundtable, “too many industries have become too consolidated,” partly because the DOJ has been chronically underfunded. Real attention to antitrust law enforcement helps us out in this regard, principally in potentially breaking up larger companies into smaller entities. Corporations also need to be monitored more closely to assure that worker rights are protected and that attempts to fix prices are thoroughly investigated.

Senator Amy Klobuchar’s (D-Minnesota) bill to reform the already existing Progressive-era Sherman, Clayton, and Federal Trade Commission (FTC) Acts would help regulators to investigate and potentially punish corporations for anti-competitive practices—such as mergers, price fixing and rigging contracts—that hurt farmers, workers, and consumers.

Biden’s billion is a good first step. At the very least, it sends a signal that his administration is willing to look critically at markets and competition in agriculture.

Still, to really get at the root of our problems in the food and farm system, we need enforcement of our existing antitrust legislation and some actual legal reform that would affect the rules of the game. How are farmers supposed to organize for change, when they’re fearful of piping up, worried about the corporate power that could come crashing down on them, destroying their livelihood?

On these points, the administration should invest billions more to rebuild the depleted antitrust division of the DOJ, and staff up with more regulators and lawyers willing and ready to research, investigate, and potentially prosecute corporate actors that sacrifice the public good on the altar of profit. If they do, we can envision a day when poultry farmers—and everyone else who toils away to put food on our tables—can once again speak freely about the companies they work for.